Step Right up for Circus Sideshow Banners, An Article From LiveAuctioneers

View the original article on Live Auctioneers here.

NEW YORK — Handpainted on canvas, vintage circus sideshow banners — some measuring up to 30 feet in width — were designed to titillate and shock circus-goers. A form of on-site advertising, they offered entry (for an additional fee, of course) to view sword swallowers, knife throwers, and fire eaters, as well as any number of hoaxes, such as “Alligator Girl” or P.T. Barnum’s infamous “Fejee Mermaid.”

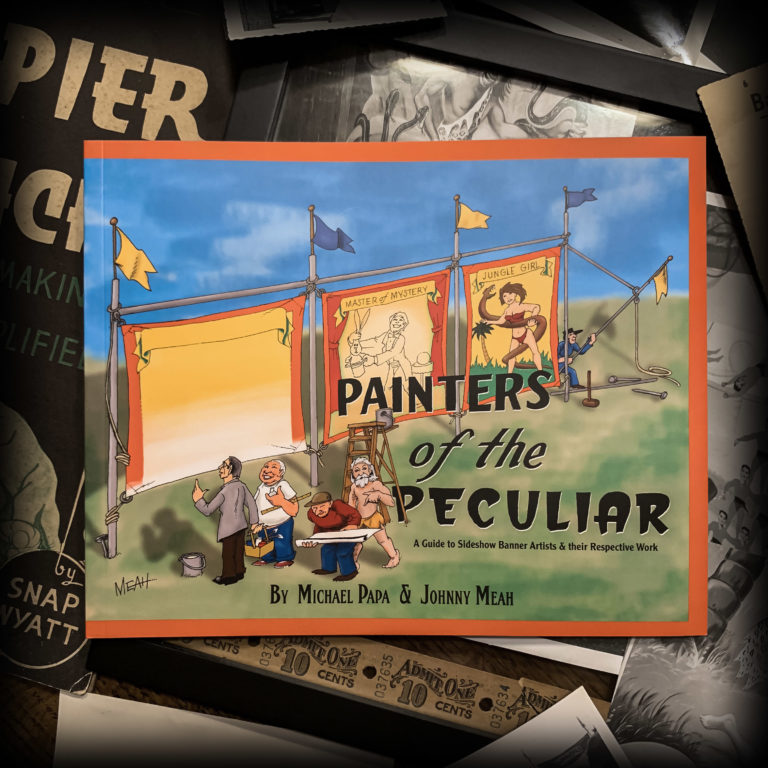

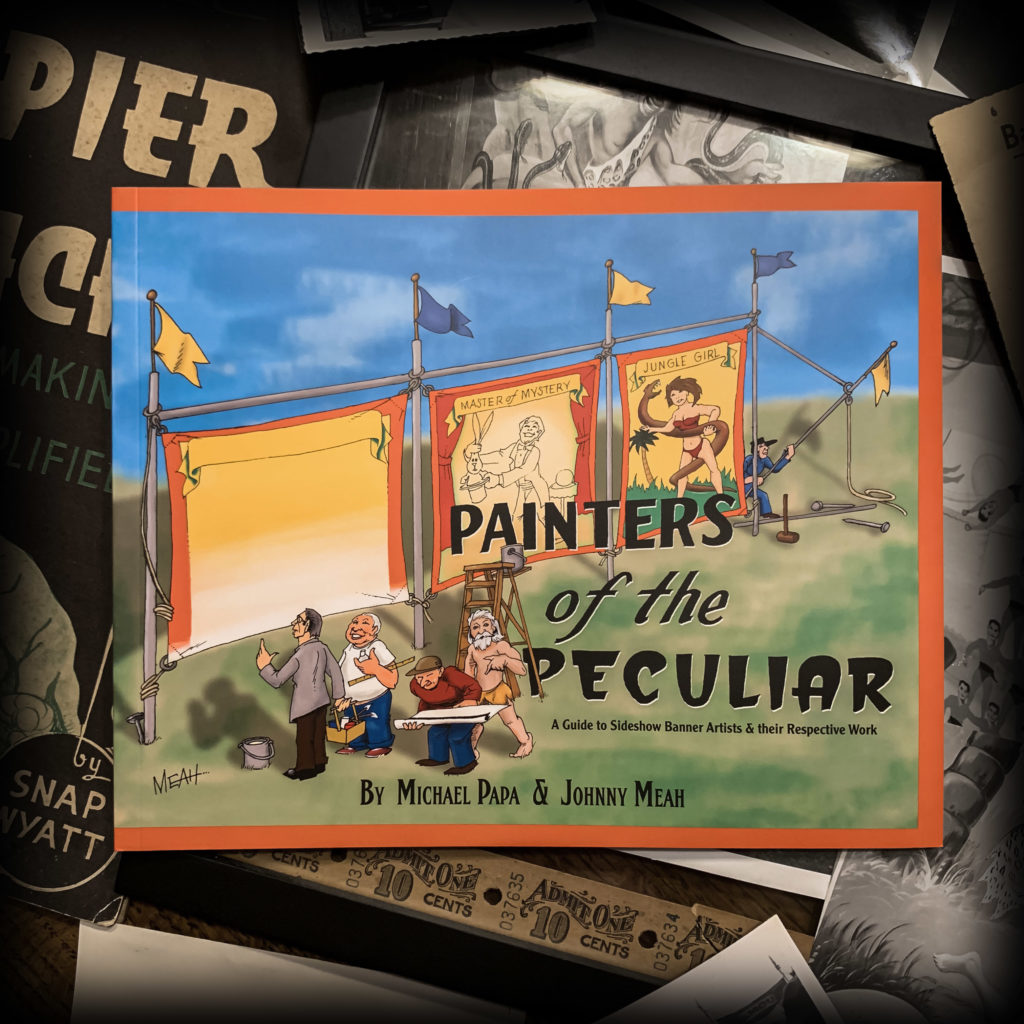

Michael Papa, who co-wrote Painters of the Peculiar: a Guide to Sideshow Banner Artists & And Their Respective Work with sideshow artist Johnny Meah and runs the Sideshow Banner Exchange in upstate New York, said banners were meant to be ephemeral. Often, after years of wear and tear during a rough life on the road with circuses, they were simply discarded. Such banners only assumed status as a legitimate art form when teacher-turned-art dealer Carl Hammer, who was an early pioneer in folk and outsider art, began collecting and selling them in the early 1980s.

“Back in the day, this stuff was not considered art — it was basically advertising. The sad thing is most of these were destroyed because people just didn’t care. People would use them until they were torn up,” Papa said.

Two of the top names in sideshow art are Fred G. Johnson and Snap Wyatt. “Fred is probably the most prolific and most well-known, and had a very distinct style,” he said. “Snap Wyatt is definitely my favorite artist. A lot of collectors prefer Snap Wyatt just because there is an air of mystery about him.”

According to the website of the International Independent Showmen’s Museum in Riverview, Fla., Johnson is considered the most widely known sideshow banner painter in the history of the circus and sideshow world. He worked for the O. Henry Tent and Awning Company in Chicago for 40 years (1934–1974), which was renowned for its sideshow banners.

Each artist had his or her own style. Philadelphia-based Material Culture, which has auctioned several banners that Wyatt created for sideshow promoter Dick Best, noted, “In contrast to Fred Johnson’s pastoral/painterly banners, Wyatt’s banners have simpler backgrounds and exaggerated Coney Island-style black outlines, giving them a pop art comic book quality…”

When it comes to sideshow banners, both size and subject matter are important when considering value. Some collectors only seek out certain types of performers, or banners by specific artists. Many banners are 8 by 10 feet and are desirable owing to their manageable size. Larger ones can be challenging to display in the average home.

The heyday for collectible banners was around the middle of the 20th century. Papa said many early banners (circa 1890s-early 1900s) were boring, often touting mundane subject matter like pony shows. “It wasn’t until the 1950s and ’60s that they really started to get dramatic and exciting, [featuring] girly shows and torture shows. It went from boring to real sideshow attractions, and you can see that in the artwork.”

Antiques dealer Philip Gallant, owner of The Antique Circus in Baltimore, Maryland, said banners with tattooed men or women are among the most desirable. “In the past, a ‘tattoo’ poster was the one I’ve gotten the most money for, and I haven’t had another one in probably 10 years,” he said.

Today, collectors seem to be avoiding banners that depict people with physical deformities and instead are seeking examples that show performers or animal acts.

In his book, Freaks, Geeks and Strange Girls: Sideshow Banners of the Great American Midway, co-author and banner dealer Edward “Teddy” Varndell, addresses the dichotomy of sideshow banners highlighting the more peculiar acts that brought out both fascination and distaste among viewers. “While we must question the spectacles that these acts (re)presented, a contemporary view of banners allows us to view their creation more thoughtfully and grasp the sideshow in relation to the ever-present interplay between perceptions of ‘low’ and ‘high’ in our culture.”

Owing to the disposable nature of sideshow banners, which were hung on stages and tents, folded up, torn and then hastily mended (often with large needles and twine), they sustained ongoing wear and tear. As a result, most sideshow banners that have survived to modern day are in fair condition and not usually much better. “The majority of sideshow banners are not in a great state because they were not meant to survive … and if they were damaged in some way, they didn’t take the time to properly repair them,” Papa said. “I’ve seen so many banners like that, it just breaks my heart.”

Gallant said the price range for a decent, but not great, banner would be $1,800 to $3,500. New collectors should look not only at the subject matter but also the condition of the canvas and its hardware. “You want to look for the leather corners with the rings in them, that’s a good indication of the older ones or at least the ones used up until the 1970s and ’80s,” he said. “It’s hard to say how to get into it. I would just be choosy, I would say set a budget and pick what you like.”

Learn more about the history of sideshow banners and their artists in the book, Painters of the Peculiar, sponsored by the Sideshow Banner Exchange. Click here to purchase.